Joachim Froese: Turned Towards the Firmament

Jan Manton Gallery, Brisbane

January 23 - March 17, 2024

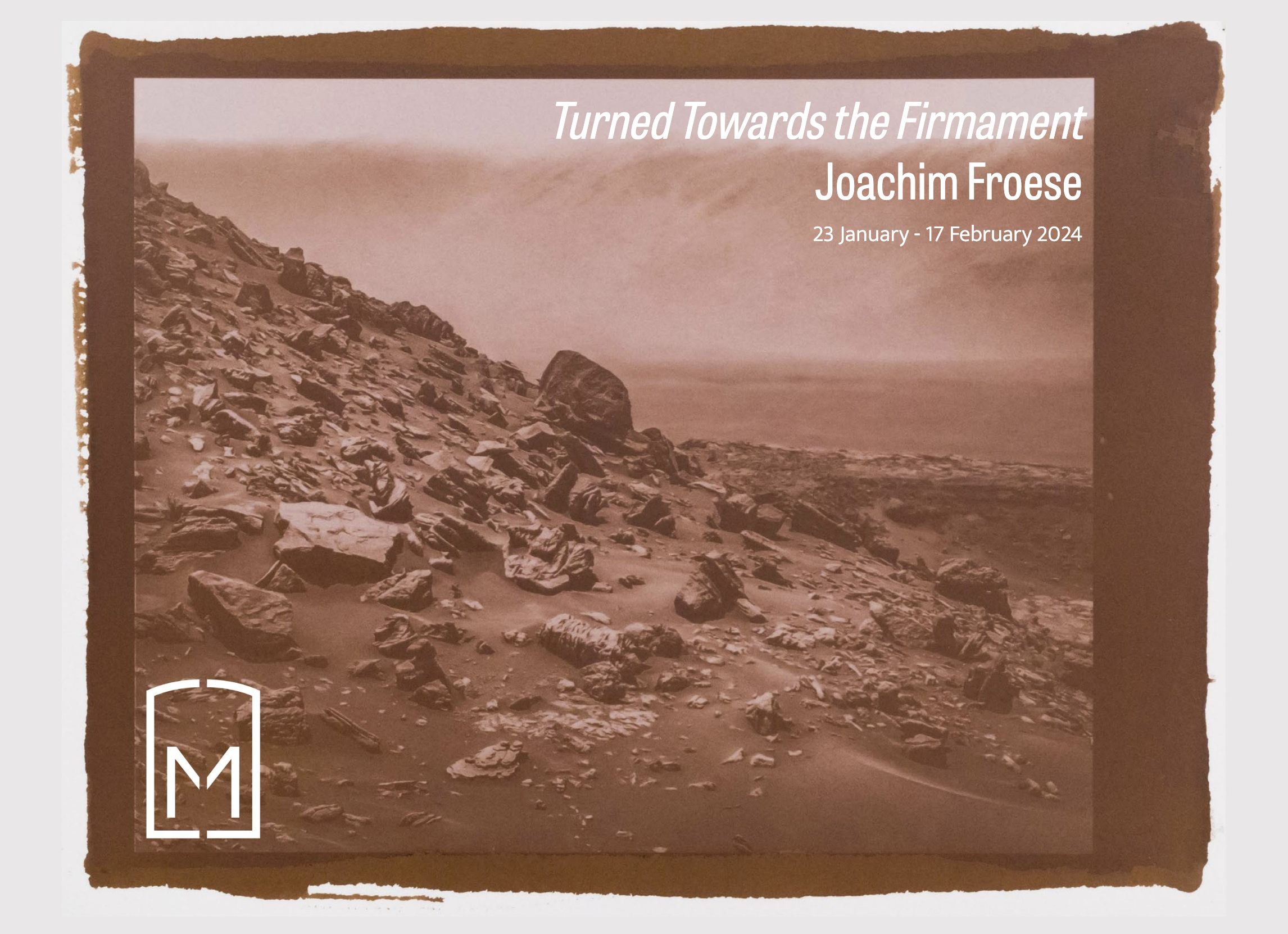

The exhibition Turned Towards the Firmament presents new work by Australian artist and photographer Joachim Froese at Jan Manton Gallery in Brisbane. Froese downloads imagery captured by NASA’s unmanned rovers on Mars and translates it into unfixed salt prints. Expanding his research into historic printing processes which he merges with cutting edge digital image capture, the work on display connects past and present of photographic technologies.

In 1839 two distinct photographic processes were publicly presented: the daguerreotype in France and the salt print in England. With all eyes that year initially on Jacques Daguerre’s process, François Arago addressed a joint session of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Art in Paris on the 9th of August to present the new process to the world. In a lengthy speech he explained the workings of the new technology and went on to muse about photography’s future applications:

‘…as soon as it is turned towards the firmament, one discovers myriads of new worlds; by penetrating into the constitution of the six planets of the ancients, we find them similar to that of our earth, with mountains whose heights can be measured, with atmospheres whose changes can be followed, with forming and melting polar icecaps, analogous to those of the terrestrial poles; with rotary movements similar to the ones here below that effect the intermittence of days and nights.’

What sounded like mere speculation in 1839 has now become reality. Since 2004 NASA is deploying rovers on Mars that depict and measure the planet’s geological features—exactly as predicted by Arago. However, the images we look at are deceptive, what resembles a terrestrial landscape, remains an alien and toxic environment.

While quoting Arago in the title for the exhibition, Froese’s focus lies on salt printing, the contemporaneous printing process on paper, announced by William Henry Fox Talbot the same year in England. Froese takes a lead from Talbot’s earliest experiments before fixer (sodium thiosulfate) became available to remove all remaining light-sensitive silver salts after exposure. Like Talbot in the beginning, Froese first washes his exposed prints in a strong salt solution, but then applies a gold toner. The resulting prints retain a distinct warm reddish hue, and they are remarkably stable. They do, however, remain sensitive to the UV light that initially exposed them.

The impermanent nature of the displayed prints is part of the conceptual approach that underpins them. It echoes their original source: fleeting data, beamed back as radio waves from a distant planet. Furthermore, it plays with the haptic experiences we bring to the photographic image – even if it was captured by a machine on another planet. What looks like a landscape we will never be able to walk in without a space suit; what looks like a rock we will never be able to touch with our bare hands. These ambiguities are emphasized by a juxtaposing series of traditionally fixed salt prints which forms the second part of the exhibition. It provides a more permanent vision of seemingly abandoned human dwellings here on Earth. However, knowing how the artist works, the digital genesis of these images should raise further doubt about the framed prints we see on the wall, even if they present a vision based on more tangible ground. All unfixed salt prints are kept in custom-made folios which feature a digital copy of the print they protect – a sculptural object displayed on the wall. To view the fragile print inside, the folder can be taken off the wall and opened under UV free, dimmed interior light. The work becomes interactive when we open the folder. For a brief moment the unfixed salt print inside can be viewed safely.

The exhibition is accompanied by an essay by Andrés Mario Zérvigon, Professor for the History of Photography at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.